Mark Zuckerberg’s virtual-reality universe, dubbed simply Meta, has been plagued by a number of problems from technology issues to a difficulty holding onto staff. That doesn’t mean it won’t soon be used by billions of people. The latest issue facing Meta is whether the virtual environment, where users can design their own faces, will be the same for everyone, or if companies, politicians and more will have more flexibility in changing who they appear to be.

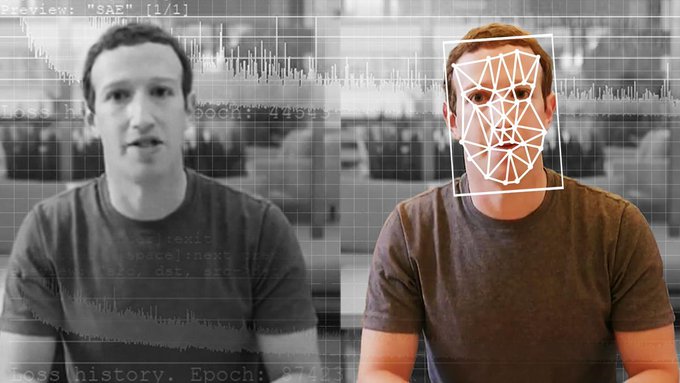

Rand Waltzman, a senior information scientist at the research non-profit RAND Institute, last week published a warning that lessons learned by Facebook in customizing news feeds and allowing for hyper-targeted information could be supercharged in its Meta, where even the speakers could be customized to make them appear more trustworthy to each audience member. Using deepfake technology that creates realistic but falsified videos, a speaker could be modified to have 40% of the audience member’s features without the audience member even knowing.

Meta has taken steps to tackle the problem, but other companies are not waiting. Two years ago, the New York Times, the BBC, CBC Radio Canada and Microsoft launched Project Origin to create technology that proves a message actually came from the source it purports to be from. In turn, Project Origin is now a part of the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, along with Adobe, Intel, Sony and Twitter. Some of the early versions of this software that trace the provenance of information online already exist, the only question is who will use it?

“We can offer extended information to validate the source of information that they’re receiving,” says Bruce MacCormack, CBC Radio-Canada’s senior advisor of disinformation defense initiatives, and co-lead of Project Origin. “Facebook has to decide to consume it and use it for their system, and to figure out how it feeds into their algorithms and their systems, to which we don’t have any visibility.”

Mots-clés : cybersécurité, sécurité informatique, protection des données, menaces cybernétiques, veille cyber, analyse de vulnérabilités, sécurité des réseaux, cyberattaques, conformité RGPD, NIS2, DORA, PCIDSS, DEVSECOPS, eSANTE, intelligence artificielle, IA en cybersécurité, apprentissage automatique, deep learning, algorithmes de sécurité, détection des anomalies, systèmes intelligents, automatisation de la sécurité, IA pour la prévention des cyberattaques.